A catcher aims to be a fly on the wall.

“If you go through a game and nobody knows you’re back there, that’s the ultimate compliment,” A.J. Pierzynski said.

It’s the only position that sees every other player on the field, including the batter, when the final out is recorded. Los Angeles Dodgers catcher Will Smith had the best seat in the house Wednesday as starting pitcher Walker Buehler showed up on his day off to record his first career save. Amid the chaos that ensued, an MLB staffer tracked down Smith to authenticate the ball. Once everything was official, Smith stuck the ball back in his pocket for safekeeping. “I got to give it to Walker,” he said.

Pierzynski knows the feeling. He watched from home plate as the Chicago White Sox won the 2005 World Series, snapping an 88-year drought, in slow motion.

White Sox closer Bobby Jenks was on the bump with a 1-2 count. Pierzynski wanted a curveball. “Bounce it,” he thought to himself. Jenks located it low in the zone, inducing soft contact by Houston Astros pinch hitter Orlando Palmeiro on a high-hopper. Pierzynski unmasked. Juan Uribe intercepted the ground ball, after having just dove headfirst into the stands to secure the second out of the inning, “à la like how Derek Jeter had done it the one time,” in Pierzynski’s words. As Palmeiro sped to first base, Uribe threw a strike to Paul Konerko. Minute Maid Park fell still, then silent when first-base umpire Gary Cederstrom punched the air.

What happens next depends on who you ask. Travis d’Arnaud said everyone disappeared in 2021, everyone except closer Will Smith. D’Arnaud flipped his catcher’s mask off mid-sprint and leapt into the arms of Smith, who twirled him in the air as the rest of their Atlanta Braves teammates converged upon the mound. Again, d’Arnaud did not notice anyone else. But then he was punched, or elbowed, or both. He couldn’t be definitive about it. He was mentally elsewhere.

“I was bombarded with emotions not only from the year before but from the past with all the playoff games and the seasons and the minor leagues,” said d’Arnaud, who referenced the Braves’ gut-wrenching Game 7 loss to the Dodgers in the 2020 NLCS. “Just everything flooded at once.”

Recalling one’s entire Rolodex of baseball lore in a single moment is an opportunity reserved for a select few. Those fortunate enough to experience the feeling also remember when they looked in the mirror and actually saw the reflection of a champion. Depending on the person, that realization may not set in until hours, weeks or months following the final out.

This is what it looks like to authenticate the final out of the World Series ⚾️

(via @MLB)pic.twitter.com/2tk6qa4uHV

— B/R Walk-Off (@BRWalkoff) October 31, 2024

For David Ross, it took years.

In the hours subsequent to Ross’ first World Series win as a member of the Boston Red Sox in 2013, he found himself at Game On, a local pub in Boston, seated with All-Star second baseman Dustin Pedroia and his wife. That year marked Pedroia’s second World Series win. So he already knew what to expect. Pedroia asked, “It hasn’t sunk in yet, has it?” Ross responded, “No.” Pedroia said, “It won’t until your career is over.”

Before Ross retired in 2016, he won another World Series with the Chicago Cubs, the franchise’s first since 1908. The historic feat prompted a trip to the White House, where Ross learned what it meant to be a champion.

“Michelle Obama starts crying, telling you stories about watching Cubs games, running home and watching with her dad, who was no longer with us,” Ross said.

“That’s the kind of stuff that makes you feel special and like a champion — different. You don’t get those until you win it all and you hear people’s memories of the moment that it happened, and what they were thinking and why they were thinking and who they were thinking of.”

Complete games aren’t a stat but an expectation of catchers, whose impact on every pitch is disproportionately larger than any other position player. They need to call the game, throw out base stealers, field bunts, cover first base and, perhaps more than anything, remain calm amid the chaos they routinely observe in nine-inning doses.

If they do well during the 162-game warmup, they get rewarded with more responsibility and higher stakes. Few make it to the final out. Many fall short.

Terry Steinbach was lucky. He did both.

Steinbach was a first-time All-Star at age 26 when the Oakland Athletics lost the 1988 World Series to the Dodgers by a 4-1 margin. He hadn’t experienced anything like the attention he and his teammates received at that stage. It was overwhelming.

“When you get to that World Series, everybody and their mother are there covering that,” Steinbach said. “So now all of a sudden, the media pits or whatever you want to call it, instead of 10, 15 people, there might be 50 to 100 people there and everybody’s going after a different angle.”

He helped the Athletics, which acquired Hall of Fame outfielder Rickey Henderson midway through the season, return to the World Series in 1989, again as an All-Star. But Steinbach was no longer wide-eyed. Everything came into a much clearer focus.

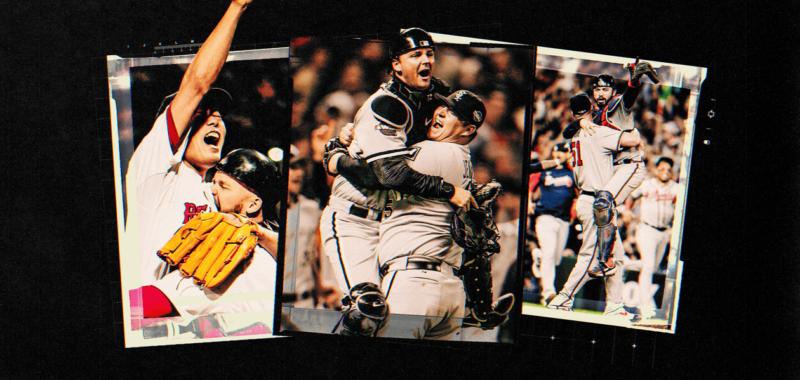

David Ross, left, celebrates with Koji Uehara after clinching the 2013 World Series. (Jamie Squire / Getty Images)

The rising action looked a bit different for Ross, a backup catcher who joined an organization fresh off of a season of turmoil. The 2012 Red Sox finished 69-93 with first-year manager Bobby Valentine, who was promptly fired following the franchise’s worst season since 1965. Ross recalls the “bad rap” the players received for their low clubhouse morale as they navigated a messy post-Terry Francona transition. The 36-year-old catcher was already wary of his fit within a team that seemingly lacked order, before he suffered a concussion early in the 2013 campaign that forced him to spend a couple of months in his Tallahassee, Fla., home away from his new teammates. He felt as though he wasn’t part of the team.

Then tragedy struck — and an almost indescribable sense of unity pervaded the city of Boston.

“When that 2013 bombing happened in the Boston Marathon, I’ve never felt more connected so fast to a city that was going through this tragedy and the first responders and how everybody rallied together,” Ross said.

Like Ross, catcher Drew Butera found himself in a backup role with a new team. But it was the Kansas City Royals, and by 2015, Salvador Perez had established himself as a perennial All-Star-caliber player. Butera was safely beyond the spotlight, until he suddenly wasn’t. He replaced Perez, who had been pinch run for in the previous half-inning, to catch the bottom of the 12th with the Royals three outs away from their first World Series win in two decades. With star closer Wade Davis getting warm, though, Butera knew he just needed to play catch.

“I was oddly calm,” he said. “I remember standing next to (pitching coach) Dave Eiland, and at that time, I think we had maybe a three- or four-run lead. I was like, ‘We just won the World Series.’”

Butera, Ross and Steinbach saw the final out into their glove. But akin to Pierzynski, a veteran d’Arnaud had to sweat out one last sequence, the ultimate culmination of a near decade’s worth of MLB service time, as a spectator.

“We got to 0-2, and in my head, I was like, ‘All right, this will be sweet to freeze him on a heater down and away to win the World Series,’” d’Arnaud said.

“Luckily, it wasn’t a homer.”

d’Arnaud said he felt like a fan, helpless. Astros first baseman Yuli Gurriel hit a ground ball to Dansby Swanson, and d’Arnaud, who technically should’ve been backing up first in the instance that Swanson opted against the force out at second, stood in place. A sudden stillness overcame him.

When Swanson fielded the ball, d’Arnaud took a peek at Ozzie Albies, who had hustled over to second base and appeared ready for a quick flip to end the game. Swanson after a quick glance, however, turned to Freddie Freeman at first.

You know the rest. d’Arnaud chalked up Gurriel’s miss on a meatball pitch to batting average on balls in play, better known as BABIP.

“Looking back, yeah, a sign of fate,” d’Arnaud said. “There’s stats for it now.”

Travis d’Arnaud, right, jumped into the arms of Will Smith at the conclusion of the 2021 World Series. (Carmen Mandato / Getty Images)

Celebration ensued, the heart of which is about the same across the board.

Catcher sprints to pitcher. Pitcher sprints to catcher. Catcher picks up pitcher, or vice versa. But Pierzynski’s summation of the parade put into perspective the distinct ripple effects felt by those who played, coached or cheered for a World Series-winning ballclub.

“It’s one of the few times in any walk of life where everybody is happy,” he said. “Every person you look at is smiling, every person you look at is excited. And that just doesn’t happen very often in anything.”

On the White Sox’s return flight to Chicago, the pilots asked Pierzynski if he wanted to watch the landing from the cockpit. He hadn’t done that before. So he accepted. Before the team touched down at Midway Airport, though, the pilots conducted a flyover. Pierzynski couldn’t believe the thousands of people he witnessed below, eagerly awaiting their opportunity to welcome home the 2005 World Series champions.

“We were the team that finally ended the Chicago curse,” Pierzynski said.

The White Sox just set the MLB record for losses in a single season and haven’t advanced past the ALDS in the decades since. Even if it’s another 88 years until next time, the history books will always preserve the 2005 team’s place in history. The same goes for the A’s. John Fisher can move the team from Oakland to Las Vegas; the Oakland Coliseum will nonetheless forever be the host of four World Series winners.

Said Steinbach: “Those memories are always going to be there, period.”

Austin Barnes, the Dodgers’ backup catcher, had caught the final out before. He knew how it felt. Smith didn’t. Having split time with Barnes when they won in 2020, Smith missed out on a moment he had mulled over for much of his life. But when asked ahead of this World Series — one of the most anticipated in recent memory — what he would do with the ball used to produce the final out, he wasn’t sure.

“I’m more excited to celebrate with the guys than worry about a baseball or whatever,” Smith said.

When the Dodgers bested the Tampa Bay Rays in the 2020 World Series, seating capacity was limited to 25 percent at Globe Life Field, the Rangers’ home venue that MLB relied upon in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. That translated to 11,500 fans. Barnes was fortunate to have his immediate family in attendance, including his dad, Dennis, who regularly picked him up from Little League games and rushed home from work to take him to Little League practices.

“It’s a lot,” he said. “I want to feel that again. You get a taste of winning, and you just want to keep going.”

Wednesday, it was a dream realized. One that most merely imagine, but nothing more.

What they see is remembered by many. But if they do it right, per Pierzynski, no one will notice they’re there.

The perks of being baseball’s wallflower.

(Illustration by Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Photos: Rob Carr, Rich Pilling / MLB, Elsa / Getty Images)