PARIS — Since it happened three years ago, Simone Manuel hasn’t gone back to watch that press conference from the 2021 U.S. swim trials. She doesn’t want to see herself sitting on that podium behind the mic, hair pulled back, white tank top, glasses. Holding back tears that were full of both despair and relief. Containing opposite emotions that ripped at her soul.

Like her journal entries from that time that she has never reread, it’s almost too vulnerable to relive or revisit. For now, at least, and maybe ever. But it still lives on in the internet — 24 minutes of her, processing in real time that she wouldn’t be defending her 2016 gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle at the Tokyo Games; 24 minutes of her trying to tell her story when, even then, it felt like she was still mid-sentence no matter how long she talked.

Dozens of questions, but all could be boiled down to three simple words: What happened, Simone?

In truth, she was still trying to understand. For weeks, she had wondered if she should put a statement out, to let everyone know that she had been diagnosed with overtraining syndrome less than three months earlier. But she hadn’t. Because every time she considered it, it only brought about more questions.

And for a mind and body already so worn down, the extra weight and cycles of doubt were too much to carry. So, Manuel said nothing. She showed up in Omaha for those trials and got off the block, which felt like a success in itself. To her. But she didn’t qualify for the 100-meter freestyle. And then came the questions.

Externally, it was devastating to process what this meant for Manuel’s swimming career. But internally, it was even harder to explain. As much as everyone else expected of her, she expected more.

“Just to know that you are falling short of your own goal, your own dream and what you’ve worked for the past five years and for it to all come crashing down is devastating,” Manuel said. “I knew I was going to have to answer questions, I knew I was going to have to explain myself. And in some ways, I knew that that was not going to be received well. Being a Black woman in America, being a Black woman in this space, I just knew it wasn’t going to be received with the empathy and care that it probably should have been. And I was afraid of that.”

She tried her best, left the dais after 24 minutes, went back to her hotel room and cried.

From Paris, now — where Manuel has already anchored a 4×100-meter relay that set an American record and on Saturday begins a race to the podium for the 50-meter freestyle — this memory feels both distant and close. Her journey to Paris — eight years after her Olympic debut — has wound in many directions, but she is here now, writing her own story.

“It feels good to be back here,” she said after the 4×100-meter relay. “I didn’t know if I would ever be performing at this level again. So just to kind of have this full-circle moment of being on this relay again from 2021 to now, but just in a happier and healthier place, I think is really special.”

The first warning signs of Manuel’s overtraining syndrome had come in late fall 2020 — three and a half years after she became the first Black female swimmer to win an individual gold at the Olympics and eight months out from the pandemic-delayed Tokyo Olympic trials. Her times weren’t where she wanted them to be. She rested, but her times didn’t improve. She went down in weight, but her times didn’t improve.

In December, she and her teammates swam sets of 50s every Thursday — 24 the first Thursday of the month, 18 the next, 12 the week after that and six the final week. With the total workload going down gradually, her times should’ve naturally improved. But they did not. By January, six months out from the trials, she was having three to four bad practices a week. Ahead of the Rio Olympics, she couldn’t recall having three to four bad practices total.

Weeks later, in a call to her mom, Sharon, she told her: “The water and I are not friends. We’re not even acquaintances. It is not welcoming to me.”

She returned to Houston and met with Dr. Rehal Bhojani, a doctor USA Swimming had recommended. On March 8, with less than three months to go until trials, he diagnosed her with overtraining syndrome. Three days later, she was back in the pool. The initial plan was to just lessen her physical load. Cut back on morning practices to see if she could sleep in and recover better.

Her times didn’t improve. Everything felt worse, and Manuel only got more frustrated. Bhojani set up a call with her coach, Greg Meehan, and told him that Manuel needed to take three weeks off completely or else her career could be over.

It was two months until trials.

At 2021 U.S. Olympic trials, Simone Manuel — battling with her training regimen at the time — qualified for the 50-meter freestyle for Tokyo. (Tom Pennington / Getty Images)

“You’re hearing her talk about her desires and her goals — and you want to encourage her to do that — but the more and more it became crystal clear that she was really, really in a bad place, I was more concerned about her health and welfare,” Sharon said. “For me, I was like, ‘Please, please, please, please, please take the break.’ Because I was more concerned that if you continue with this, you’re going to get yourself in a spot where you will never be able to do this again.”

On April 17, she got back in the pool. Trials began June 5.

There, the reigning 100 free Olympic champion didn’t even make the final, where the top two finishers qualify for the Games. She finished ninth. But she made the Olympic team in the 50 free, which allowed coaches the option of using one of the best relay swimmers — even if she hadn’t swum the 100 free well at trials.

In Tokyo, still exhausted, Manuel anchored the 4×100-meter freestyle relay, leading the Americans to a bronze medal. She failed to advance to the final in the 50 free individual event. On Aug. 2, her 25th birthday, she returned home from the Olympics with just that one bronze medal to show for it. All her previous Olympic medals from Rio had been either gold or silver.

Days later, Bhojani asked her how much time she thought she needed off from swimming, from all activity.

What do you need, Simone? He asked.

“He gave me — in that moment — ownership of my career,” Manuel said, “and I think that catapulted me into how I healed from it and how I have tried to approach my career since then.”

At least until January, she replied.

In early January 2022, she met with Bhojani over Zoom. Even virtually, her eyes looked better, he told her. It wasn’t just her eyes. She felt different, better. Like maybe she could start over again and make a run for Paris. She had two and a half years to go from Square One to the Olympics.

She decided to look for a new coach and thought of it as her “second recruitment.” When Bob Bowman got her call, he was shocked. Though he became world-famous for training Michael Phelps, he didn’t exactly have a reputation for training sprinters. He didn’t think there was any chance that she’d want to work with him.

So, with not much to lose, he was blunt and honest with her.

“It’s going to be a long and difficult and frustrating process, and if you’re not up for that, don’t start it,” Bowman remembered telling her. “It is going to take every day of the next two years to get you to where you want to be.”

She was in. For the first few months, she trained at a 24 Hour Fitness in Northern California. She was surprised to find that you could only reserve lanes for 30 minutes at a time. Even when she approached the manager (“I usually don’t pull that card,” said the Olympic gold medalist), she was told that exceptions were made for no one.

So, Manuel began her road back to the Olympic lanes in an over-chlorinated pool with kids in swim class and retirees doing water aerobics. It didn’t take long for her to become a regular, and when the retirees found out she was training for the Olympics, they happily shared their lanes and became her cheering section.

For that first year, Bowman told Manuel, she was training to relearn how to train. Once they established that baseline, she’d train to compete.

In August 2022, she moved to Arizona to train in person with Bowman.

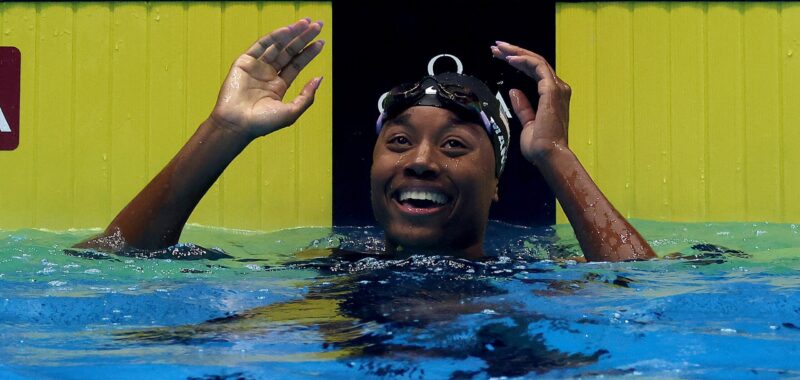

Back in the 50-meter freestyle at the Olympics, Simone Manuel’s pursuit of individual gold begins Saturday in Paris. (Maddie Meyer / Getty Images)

“She had problems in the early part, because her standards are so high,” Bowman said. “And when you know what your best training is like, and you also are quite aware of what you’re doing now, no matter what she did, even though it was better than yesterday, it would not be good enough. So finally, we had to come to this agreement that our goal is progress, not perfection.”

After almost a year of their partnership, Manuel entered her first race. In May 2023, at a meet in Mission Viejo, Manuel didn’t finish above third in any of her races. She got out of the pool, disappointed, and Bowman pulled her aside and said, “If you had a friend who had gone through what you went through, and just did what you did, what would you tell them?”

Manuel took some time off, and when she returned to the pool that August, she felt different. In control. Ten months out from the Olympic trials, she and the water were friends again.

For her entire life, affirmations had been a part of daily routine. When Manuel was nine, she saw her first Olympic medal at a swim event. She got to try it on. When she got in the car afterward, she told her mom, “I’m going to the Olympics.”

Before every world championship and Olympic medal she has won — 19 in total — she told herself she would. Before every broken Stanford, American and world record she has claimed, she told herself she would. When she was at her best, she believed 90 percent of what she told herself, giving herself 10 percent grace, understanding that in sports anything can happen.

But in the darkest of her times, that flip-flopped.

“When I was going through this tough experience, it was like I’m 90 percent lying to myself,” Manuel said, “and 10 percent things could still be achievable.”

In Indianapolis in June, at the 2024 U.S. Olympic trials, Manuel was back at 90 percent believing her affirmations and feeling as good in the pool — as good of friends with the water — as she had in a long time. She carried so much with her but she also felt free. She wanted to swim with no pressure. And she did. She missed the team in the 100 free, but on the final night of the trials, she took gold in the 50 free, swimming a time that was just six-hundredths of a second off her personal best she set in 2015.

“I went through so much. … It’s so loaded, the day-to-day experiences and thoughts that I had, and the challenges that I faced physically,” Manuel said. “And just to make it out on the other side — I have a lot to be proud of, to be back on an Olympic team. … I think it’s really important to just recognize that the journey that I took, the resilience and the perseverance to continue is a gold medal in itself.”

Simone Manuel, Gretchen Walsh, Torri Huske and Kate Douglass pose with their silver medals from the women’s 4×100-meter freestyle at the Paris Olympics. (Al Bello / Getty Images)

(Top photo of Simone Manuel celebrating her 50-meter freestyle victory at U.S. Olympic trials: Al Bello / Getty Images)