Thirty-five years after the winningest season in Dartmouth soccer history, players from that era of the school’s program found a reason to reconnect last month.

Though many of them have stayed in touch throughout the years, time has pushed them away from each other, like it does with many old friends. Their winning didn’t stop when they graduated from college. Some became successful businessmen. One is part-owner of an MLS team. Another had a run as an actor on “Melrose Place.”

The collective success is unusual for any group of college friends, even one from the prestigious Ivy League. That success conditioned them to expect great things from their old teammates. Even so, the news of Bill Chisholm’s agreement to purchase the Boston Celtics grabbed their attention. They reached out to each other. They contacted their old coach, Bobby Clark, a legend of Scottish soccer. They reflected on their two Ivy League championships and their march to the 1990 NCAA Tournament Elite Eight.

Together, former Dartmouth players celebrated Chisholm, their old teammate and lifelong Boston sports fan.

Not much is known publicly about the incoming Celtics owner, who typically kept a low profile until agreeing to buy the franchise last month.

As well as just about anyone, Chisholm’s former soccer teammates can predict what type of culture he will aim to cultivate in Boston and what types of values he will hold dear. They were his roommates, his friends and his earliest business partners. Not every piece of Chisholm’s leadership style with the Celtics will trace back to his days in cleats in Hanover, New Hampshire, but he still lives by many of the lessons he learned there.

“It’s part of my life that was certainly special,” Chisholm said. “But it’s also been so formative for me in business and just everything you do.”

According to the players on the team, Dartmouth’s soccer magic started with their coach, Clark.

Clark’s resume is long. After leading the Dartmouth program to its best years ever, he did the same at Stanford before winning a national championship at Notre Dame. Before coaching, he starred as a goalkeeper for Aberdeen in the Scottish Premiership, setting a British record for consecutive shutout minutes (1,155) that held for decades before it was broken. In 2002, Abderdeen named Clark one of its top-25 players of all-time.

“He’s iconic,” said former player Richie Graham, now a part-owner of the Philadelphia Union alongside Kevin Durant, among others.

At Dartmouth, Clark quickly turned around a program that went through a 2-11-1 season shortly before he arrived.

“I think most importantly he built a culture,” said Chisholm. “And he built a culture of winning and a culture of togetherness and a culture of attention to detail and … those things are hard. Those things are hard to change. And he did it in a remarkably quick way and then it just maintained and it’s continued on.”

Clark taught his players about more than the game. After they trailed dirt and grass into the locker room, he would make them clean it up. When they went on bus rides, he would make sure they thanked the driver and left no trash in the vehicle. Once, a player arrived late for the bus. Clark left him behind.

Graham said it’s no coincidence so many of Clark’s players have achieved success after college. Gregg Lemkau, the goalie on the 1990 team, is the co-CEO of BDT & MSD Partners, the merchant bank that brokered the Celtics sale to Chisholm. Tommy Clark founded Grassroot Soccer, a nonprofit using the sport as a tool to assist children in Africa. Andrew Shue co-founded a full-service creator media company named Raptive after a successful acting career. Josh Stein, who graduated from Dartmouth in 1988, is the governor of North Carolina.

“For me, it was like winning a lottery in a way (playing for Clark),” Graham said. “He was a values guy. He was a work ethic guy. No one was given anything, and I think a lot of those attributes probably shaped a lot of that group of guys, including Billy.”

As a player, Clark learned from some of the best minds in the sport. Alex Ferguson, regarded as one of the best managers ever after finishing his career with a record 49 trophies, including many won during his time with Manchester United, coached him at Aberdeen. Ferguson’s influence echoed throughout the Dartmouth program.

“Ferguson, his secret — it’s not some huge secret — but it’s really treating everybody with real value, making sure everybody feels that value on the team,” said Shue. “So, that was how Bobby operated. And I think that if anybody wants to know how Bill will operate as a team owner, they should just study how Bobby Clark operated. And I’m pretty sure Bill has the model ingrained in him. We all do.”

Clark had a strategy to utilize Chisholm as a Dartmouth senior. He would typically start at striker and play the first 20 or 30 minutes of each match before giving way to the players, including Graham, who tallied most of the goals.

“Bill was really one of the more selfless guys,” said Tommy Clark, the coach’s son and one of Chisholm’s teammates.

As Graham described it, Chisholm operated like a wide receiver who would take the top off the defense so teammates could operate underneath. Chisholm only netted one goal over 12 career appearances, according to a story in the New Hampshire Union Leader, but he took pride in performing his role. At roughly 6-foot-2, according to two of his teammates, he was big enough and physical enough that defenses couldn’t feel comfortable allowing him to run free. Among other strengths, he had a willingness and ability to outwork people. Chisholm aimed to exhaust the opponent and loosen up the defense for later in the match.

“That’s what a lot of those runs are about,” said Graham. “So, you might do a ton of those runs in the game, and you only get the ball a couple times. It’s like the quarterback’s not giving you the ball all the time, but those runs that you’re doing, first of all, they tire out the defense, but they also create opportunities for others.”

“He would just run,” added Graham with emphasis. “And you need someone who’s actually willing to do all that work day in and day out.”

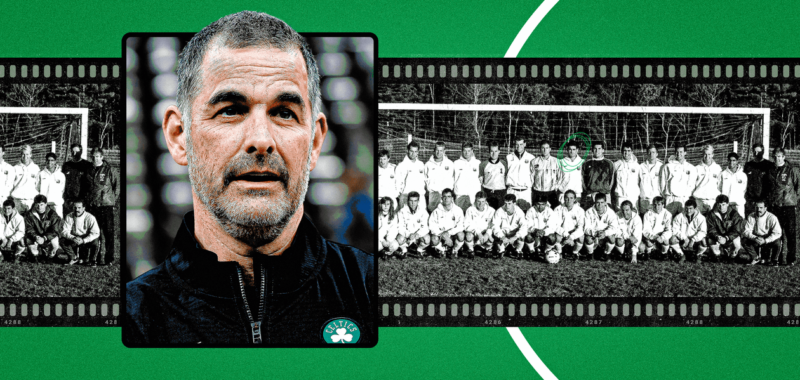

With senior day approaching this weekend, we throw it back to 1990 with this picture that includes alumni Bill Chisholm, Richie Graham and Gregg Lemkau.

This team won the 1990 Ivy League Championship and advanced past the first round of the NCAA tournament. pic.twitter.com/R3JSrIHLyt

— Dartmouth Men’s Soccer (@DartmouthMSoc) November 5, 2019

Chisholm embraced the necessary work. Clark pushed his players hard with VO2 max tests and two-mile runs, among other conditioning drills. Following one of Chisholm’s first such tests at Dartmouth, he remembered running straight toward a trash can because he felt sick. But over his time at school, Chisholm proved himself as one of the team’s best-conditioned athletes. His personality transformed when it was time to compete.

“He’s a very, very kind person,” Graham said. “He’s easy to get along with; he laughs. He’s a good guy in a team environment, but I just remember that he had a different personality when he was on the field than maybe when he was off of it. And I mean that in the best way.

“I really actually loved that about him. Excuse my French, but he was a f—ing competitor. But then super nice and friendly and that’s the best way to describe it.”

Chisholm needed to accept he wouldn’t be the star, as he had been at The Brooks School in North Andover, Mass. It took him years to carve out a consistent role on the varsity team at Dartmouth. Even before he accomplished that, he did everything Clark asked him to do.

“You’re hoping you’re going to make them good people for life,” Bobby Clark said. “If they’re good teammates, they will be good workmates later on in life. And Billy, you couldn’t get anyone better than him.”

During Chisholm’s time at the school, Dartmouth captured the Ivy League title in 1988 and again in 1990 while going a school-record 14-2-2. In the latter season, the Big Green knocked off Vermont and Columbia in the first two rounds of the NCAA tournament to advance to an Elite Eight matchup with Alexi Lalas’ Rutgers side on Nov. 24, 1990.

All these years later, the players from that Big Green squad still hold onto their final game together. Though Lalas went on to become a World Cup star for Team USA, TV analyst and MLS general manager, the Dartmouth players still think of him as the guy they should have beaten to reach the national semifinals.

“He wasn’t that good,” said Lemkau. “If you talk to him, you can tell him I said that.”

A New York Times story about the match noted that Lalas was off that day. He said he was shortly removed from a burst appendix that forced him to lose 35 pounds and spend a month in hospital.

“They were a surprise given the realities of the Ivy League,” Lalas said. “And all these years later, I still live rent-free in his head.”

That game against Rutgers was Chishom’s last for Dartmouth. It ended in agony.

He tore his MCL in about the 15th minute of a 1-0 loss. After trying to run off the injury, he realized he wouldn’t be able to stay on the pitch.

“My leg felt like it was in two pieces,” Chisholm said.

He said his injury probably didn’t impact the match much. Chisholm said he was already nearing the end of his stint. Even if he had stayed healthy, he would have exited the match shortly after he did. Bobby Clark remembered the match far differently. He said the injury threw off Dartmouth’s usual substitution pattern.

Some of his teammates still wonder “what if?” when thinking about that match, but Chisholm looks back on it with a different perspective. He believed his team was up to the task against Rutgers. If one or two bounces had gone the other way, Dartmouth would have advanced to the final four for the first time in school history. That would have been sweet, but Chisholm found value in his failures as well.

“I probably learned more about myself and life lessons from losing some games and having some challenges getting on the field… than from some of the victories,” Chisholm said. “Not that I would (want to lose); the victories are pretty special as well, but the way it happened, it’s certainly made an impact on me. And in the same way that maybe a few of those things bounce the other way or the other, I don’t think I’d be a different person, but you’re kind of an accumulation of all those little experiences.”

Current Celtics owner Wyc Grousbeck, left, with Bill Chisholm and his wife, Kimberly. (Winslow Townson / Imagn Images)

The house in Hollywood Hills had a pool in the backyard. That’s where Chisholm, Shue and Lemkau shifted from teammates to roommates. Though Shue graduated from Dartmouth two years earlier than Chisholm and Lemkau, they reunited when they moved to Los Angeles after college.

It was a chaotic time to room with Shue, who was breaking onto the television scene in his role as the “Melrose Place” character Billy Campbell. In 1993, he was featured alongside Cindy Crawford on the cover of People Magazine’s “50 Most Beautiful People in the World” edition.

“He was just like one of us,” Lemkau said. “And then all of a sudden … six months later is on the cover of People Magazine with Cindy Crawford.

“People are like, what the hell happened, dude? It was a pretty wild time.”

“He always had that magnetism,” Chisholm said. “And so, if you step back, it wasn’t that surprising news (for him to be) in the situation. But nonetheless, I mean, you’re 20-something years old and rooming with someone like that — with a true, true celebrity.”

Though Shue’s sister Elisabeth starred in “The Karate Kid” and a long list of other films, he didn’t have dreams of becoming an actor himself. He said his break in the industry came after The Hollywood Reporter featured a picture of him and his sister. Somebody called his sister’s agent wondering if he was an actor. In a white lie, she said yes.

When he returned from Zimbabwe, where he briefly played professional soccer, he spent a year in New York auditioning and training with his sister’s acting coach. He told himself he would try acting for two years. As he quickly became a sensation, he said he was grateful to live with two college teammates who kept him grounded and gave him grief.

Chisholm couldn’t have expected to become part of such a ride.

“Kind of like the whole thing with the Celtics is for me right now,” Chisholm said. “It was a little surreal. It would just be incredible. You’d be like, ‘Hey, you want to watch a show tonight?’ And you sit next to him… and there he is on TV. And we would walk around town and he used to wear a baseball cap everywhere because he was that popular.”

Around that time, Shue entered into his first entrepreneurial venture, a daily newspaper detailing the 1994 World Cup. He and his business partners brought on Chisholm as the CFO. After initially thinking they would make readers pay for the newspaper, they eventually decided to give it away for free. Handing out newspapers in places like airports and hotels, they worked their way into a circulation of 200,000, according to Shue.

“It was a 24-day project,” Shue said.

Shue said they earned $300,000 in profit. It was likely Chisholm’s first successful venture, but far from his last. The same steadiness that convinced his friends to put him in charge of the finances helped him advance rapidly in his career.

“He’s by the book,” Shue said. “Kind of a buttoned-up person who when you meet him; you get a sense of like, OK, this guy’s not going to mess up the numbers. He was the straight arrow, the more straight arrow of the bunch.”

Actor Andrew Shue at a charity soccer match with former NBA star Steve Nash in the background. (Joe Corrigan/Getty Images)

What type of owner will Chisholm be? The question has been on the minds of Celtics fans since he and a group of fellow investors agreed to purchase the franchise at an initial valuation of $6.1 billion. As great as the team has been in recent years, he will be stepping in at a difficult time with the threat of an enormous luxury tax bill looming.

“He’ll be a strong, quiet leader,” said his former coach, Clark.

After the way some new team owners have stepped in and orchestrated or at least overseen destructive changes (hello, Phoenix and Dallas), there is room to worry about the effects of the franchise changing hands.

Chisholm’s old friends believe he will be prepared.

“He’s no dummy, and I’m sure that he’s got a plan, and he’s put that into the calculus,” Graham said. “I think he’ll be surprised probably by the limelight stuff (that NBA owners encounter) and he’ll push it away, but I’m sure he’s thought through sort of exactly (that issue) because it’s a critical financial issue to sort of evaluate before you make a bid.”

Graham believes Chisholm could probably rattle off old Danny Ainge statistics off the top of his head. Chisholm’s Boston fandom didn’t end with the Celtics. According to Lemkau, Chisholm once dreamed of becoming the Red Sox GM.

Many kids in Massachusetts do. Not many grow up to purchase the Celtics.

The franchise already has its own successful culture to carry on. By all indications, Chisholm intends to preserve it.

From conversations with people in various aspects of the organization, he senses everyone is pulling in the same direction. He believes head coach Joe Mazzulla and GM Brad Stevens have constructed a team filled with people “bought in on every level, just completely buying into the team concept, understanding and being appreciated for the role that they play.”

“I think when I look at it not just over history, but the legacy that this group is building, that’s the real sustaining part,” Chisholm said. “Because people come and go, people get injured and you kind of miss things here and there, whatever. But the thing that really keeps it together is that culture. And that’s what Bobby Clark built, and that’s what I think the Celtics have done.”