Iran is now perilously close to acquiring nuclear weapons. It possesses the ingredients for a rudimentary nuclear explosive device in a matter of several months and likely could achieve an arsenal of deliverable warheads within a year.

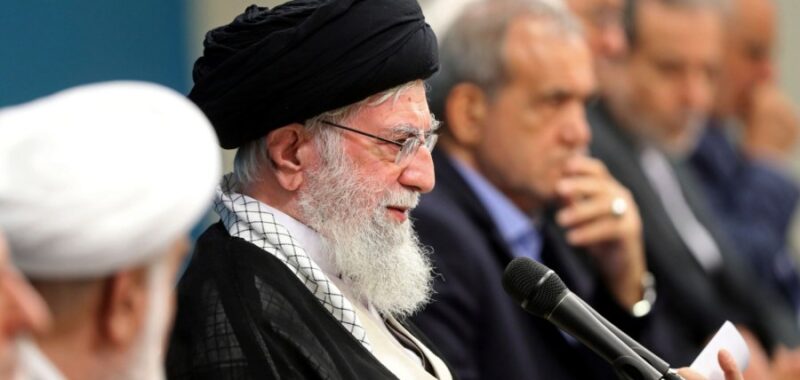

The U.S. intelligence community is losing confidence that Iranian leaders are not getting ready to cross this Rubicon, even though it had until recently assessed that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has not yet decided to go nuclear. But Iran’s Oct. 2 missile attack on Israel and the latter’s likely retaliation could change this calculus, unleashing a chain reaction in the process.

To avoid that outcome, the U.S. must take the lead in seeking an off-ramp with Iran that constrains its nuclear activities well short of a bomb. It could try to build on a mandate that Khamenei has given newly elected President Masoud Pazeshkian to resume nuclear negotiations with the U.S. and its Western partners.

What might a nuclear off-ramp entail?

The U.S. aim should be both to tame Iran’s nuclear ambitions and arrest the prospects of further conflict escalation in the region. The complex issues involved, coupled with Iran’s negotiating style and the U.S. difficulty in offering durable commitments, are bound to make such negotiations long and complicated, straining the limits of what politics in Washington, Paris, London, Berlin and (perhaps) Beijing can bear.

Making matters worse, compared to the last attempt at nuclear negotiations, Tehran now enjoys considerable backing from Moscow and its nuclear program is far more advanced, though its regional proxies and allies (Hezbollah, Hamas and the Houthis) have been seriously diminished.

By far the biggest challenge for negotiators will be the inevitable linkages among nuclear activities, Iran’s regional behavior, and its assistance to Russia’s war in Ukraine. The inability to satisfactorily address all three is likely to further hinder the Western ability to offer Iran sanctions relief in return for nuclear timidity.

Calibrating expectations is therefore essential, all the more so as the U.S. is now in a period of election-imposed political paralysis likely to last well into spring 2025, regardless of the election results.

A nuclear off-ramp requires a two-step process: immediate stopgap measures to prevent further escalations, followed by more comprehensive and enduring arrangements.

Nuclear stopgaps could comprise tacit understandings of activities or actions from which Tehran should desist — such as refining and testing weapons designs, enriching uranium to 90 percent U-235 and converting its highly-enriched uranium to metal. Enumeration of these understandings should reinforce the Iranian leadership’s appreciation that any further step toward a deliverable nuclear weapon would not go undetected.

In return for this nuclear forbearance, Washington could promise to dissuade systematic Israeli attacks on Iranian nuclear installations.

Similarly, negotiators could work out modest interim stabilization measures for Iranian regional activities and support against Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. The bargain could entail Washington’s commitment to refrain from tightening oil sanctions against Iran (and perhaps symbolically easing others) so long as Tehran holds back from scaling up (in quantity or quality) its military support for Russia.

Further, Washington could promise to dissuade Israel from scaling up the aims of its land offensive in southern Lebanon if Iran does not extend greater support to all its endangered proxies in the region.

Behind this short-term bargain would need to be an implicit threat from the West of what happens if Iran does not comply: stepped-up sanctions enforcement leading to full sanctions snapback, covert actions aimed at destabilizing the Iranian regime, interdiction of arms supplies to proxies and bolstering Israel’s offensive capability to retaliate against Iran.

An interim de-escalation bargain would then set the stage for formal negotiations to begin next spring on a more durable agreement. Such exercise would be far easier if progress toward a cease-fire in Ukraine or Gaza were agreed upon by then.

But even if both proved elusive, the logic of undertaking a comprehensive nuclear-specific negotiation would still be compelling. For if Iran goes nuclear, it could unleash a proliferation chain reaction that spurs bomb programs by Saudi Arabia, Egypt or Turkey.

There is also the urgent matter of the October 2025 expiration of the United Nations provision for snapping back full international sanctions on Iran, which creates something of a negotiating deadline.

At the core of nuclear negotiations should be an effort to codify, cap and introduce additional verification measures to check Iran’s weapons threshold status. Although the negotiation would focus on Iran’s program, these should be conducted with an eye toward establishing constraints and a transparency template applicable to any state that similarly accrues advanced nuclear capabilities up to the threshold.

The stakes are high and the time to act is now. Realism mandates choosing a pragmatic course that stands a chance of rare bipartisan support in Washington. Not least because it creates space for the next administration to subsequently chart its own course of action on Iran.

Ariel E. Levite is a senior fellow at the Nuclear Policy Program of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Toby Dalton is the co-director of the Nuclear Policy Program of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.