The lure of legacy often motivates outgoing administrations to tattoo the legal landscape with their brand in as many ways as are available in their final hours. These are often called midnight regulations, midnight monument designations, midnight pardons, and the like.

While the ink is spilled on each of these categories during every presidential transition, one category is seldom discussed. We must beware of the midnight solicitor’s general opinions.

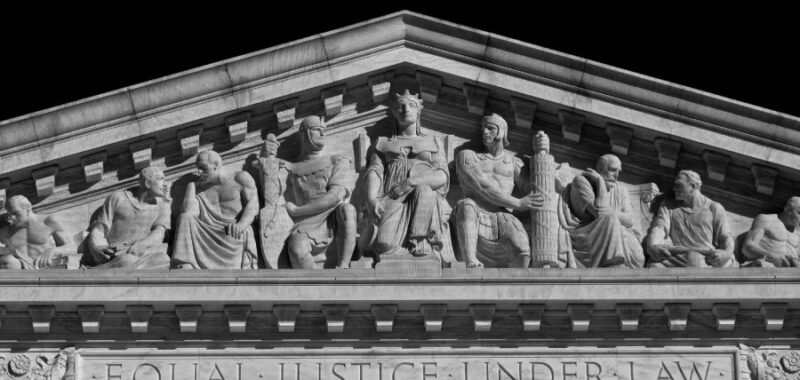

The president appoints the solicitor general with the advice and consent of the Senate and presents the official legal position of the United States government in cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. The solicitor general regularly files briefs unsolicited, standing beside other government agencies in their litigation.

In cases under review this term, the solicitor general has filed 22 briefs of this type, with more expected in pending cases.

There has also been a longstanding practice at the U.S. Supreme Court where the Supreme Court sometimes “invites” extraneous legal advice by asking the solicitor general for the administration’s legal position in cases where the U.S. is not yet even involved. Indeed, the solicitor general has been nicknamed the 10th justice, reflecting just how influential he or she can be.

These solicitor general briefs are particularly suspect vehicles for last-minute influence on the long-term progress of the law. Right now, there are at least seven cases where the Supreme Court is waiting to receive briefs it invited the solicitor general to file. And these cases involve some pretty big issues.

For example, the Supreme Court requested the solicitor general’s views in two cases involving interrelated issues of federalism, climate change litigation and the scope of judicial power.

In Alabama v. California, 19 Republican state attorneys general filed an original complaint directly in the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that Democratic states should be enjoined from suing oil companies over emissions and promotion of fossil fuels.

The complaint alleges, among other things, that these state court actions are a de facto regulation of the U.S. and global energy sectors, harming the plaintiff states and interfering with exclusive federal powers. On Oct. 7, the Supreme Court ordered that “The solicitor general is invited to file a brief in this case expressing the views of the United States.”

Also before the nation’s highest court is whether to grant petitions for certiorari to review a decision from the Hawaii Supreme Court that recognized a broad theory of liability to hold energy companies liable for the effects of climate change. These petitions for certiorari in Sunoco v. Honolulu and Shell v. Honolulu were filed by the defendants in February.

Like the October request in the state attorneys general case, on June 10, the U.S. Supreme Court put off its decision on whether to grant the petition in the Honolulu case and asked the solicitor general to weigh in with the administration’s legal view of the case.

We are awaiting responses to the Supreme Court invitations to the solicitor general in these two and several other hot-button cases, most made by orders on June 10 or Oct. 7. These include a case involving redistricting in North Dakota and the creation of Native American subdistricts, implicating interpretations of the Voting Rights Act, redistricting law generally and the meaning and scope of the Equal Protection Clause.

Another case requires an interpretation of a split between state supreme courts on what is known as the “Dormant Commerce Clause,” regarding whether states have a duty to credit the taxes paid in other states when calculating a citizen’s tax obligations.

In another important federalism case, the court has asked the solicitor general to weigh in on whether the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 preempts state laws that regulate pharmacy benefit managers and whether Medicare Part D preempts state laws that limit the conditions pharmacy benefit managers may place on pharmacies.

Yet another case where the outgoing solicitor general has been asked for an opinion will determine whether government officials have immunity in their individual capacity from lawsuits involving violations of religious freedoms under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act.

All midnight actions risk that a lame-duck president or outgoing administration gets to have an outsized influence on the direction of the law in this country, rushing through whatever they can in as durable a way as possible to leave their mark. There is an especially strong temptation to handcuff the incoming administration of an opposing party with legacy actions that are difficult to unwind.

These actions can have a significant effect on the ability of a new administration to pursue their own policy priorities or advance their own interpretations of the law and consequently can have a form of “dead hand” control with lingering effects on the country as a whole for years to come.

The Biden administration should resist this temptation and hold off filing invited solicitor general briefs — which are often given a long timeline for filing anyway — leaving it to the incoming administration to express the legal position of the U.S.

And the new administration would be wise to request leave to file an amended brief in every one of these cases immediately upon inauguration. Not filing in these cases would avoid the instability of potentially conflicting views and conserve judicial resources.

A strong case can be made in many of these cases that the new administration will be the one that must live with the court decisions that affect federal power and should, thus, have a more influential say than the outgoing administration. To the extent the climate change cases hamper energy policy or constrain geopolitical solutions to climate change, for example, it is the new administration that should opine on the nature of the impact of these cases on the United States government.

Finally, if the Biden administration’s solicitor general does file briefs in these cases, the midnight temptations should color our reading of the interpretations they offer. An administration on its way out is more likely to advance wish-list interpretations of the law in its advice to the court.

It is not just a last chance to make a mark —they also do not need to take the blame for any negative effects from dangerous moves in law.

Donald J. Kochan is a professor of law and executive director of the Law & Economics Center at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School.