LOS ANGELES — Limpin’ lizards, here came Freddie Freeman, bounding around third base, barreling toward the plate like a car low on motor oil and short on brakes. He runs as if he stubs his toe with every step. He runs as if his cleat is filled with thumbtacks. He runs as if he watched an instructional video from Bruce Bochy.

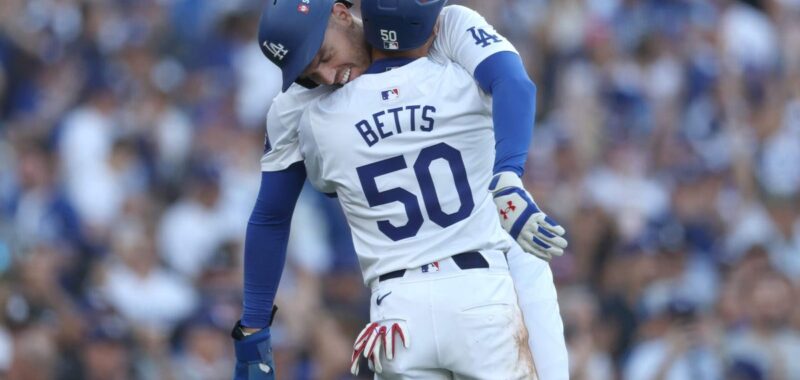

He runs as if his right ankle is sprained and swollen and stinging with each step — because it is. You can see it in his face. You can see it in his gait. And you could see it in the way he lumbered into the waiting arms of Mookie Betts on his looping dash home in the first inning, a tone-setting scamper in the 9-0 Dodgers stomping of the Mets in Game 1 of the National League Championship Series.

“I gave it all I’ve got,” Freeman said. “And I needed Mookie to stop me from falling over at the end.”

The pain and the stiffness and the general inability to motor did not prevent Freeman from scoring on Max Muncy’s single. His jaunt symbolized his club’s pluck. The Dodgers are battered and bruised — but when their offense clicks as it did on Sunday, they might just be better than every team in baseball. Only four are left. The Dodgers are the closest to reaching the World Series.

Freddie Freeman went to 2 for 3 with a walk, but will he play in Game 2? “Until I hear otherwise,” manager Dave Roberts said. (Kevork Djansezian / Getty Images)

Freeman helped clear the path in Game 1. He was one of three Dodgers to take a walk as Mets starter Kodai Senga stumbled in the first inning. When Muncy splashed a single into center, Freeman endured a 180-foot ordeal to score. He supplied two more hits, including an RBI single in a three-run fourth inning. In the eighth, as has become a custom, manager Dave Roberts replaced him in the field. Freeman ended the evening as he has ended most of them this postseason: Unsure if he could play the next day.

“We have the utmost respect for him and the way he goes about it,” outfielder Kevin Kiermaier said. “He’s an absolute dog.”

His ankle creates a daily crucible for Roberts. Freeman hurt himself sprinting through the bag on Sept. 26. The doctors told him the injury required four to six weeks of rest. He returned to the field after eight days. He called this injury “the hardest thing” he’s had to deal with on a baseball field. And that was before he tried to play on it.

With Game 2 slated for Monday afternoon and with left-handed starter Sean Manaea starting for the Mets, Freeman might not be in the lineup. The quick turnaround left him short on time. His pregame routine requires nearly five hours of treatment from physical therapist Bernard Li. “Me and Bernard Li might be sleeping here tonight,” Freeman said.

“My expectation is that he’s going to be in there,” Roberts said, “until I hear otherwise.”

By now, Freeman has gotten used to this routine. This year, he started filling out crossword puzzles, a habit practiced by his elders when he debuted with the Atlanta Braves in 2010. He is 35 now. “When I first came up, I envisioned that as older guys in the clubhouse, doing crosswords,” he said. “Now I’ve become one.” On the training table, he kills time filling in the blanks. For the most part, though, his rehab is not a passive experience. The exercises test his tolerance for pain and his capacity for mobility.

“Believe me, it’s not me just laying there in comfort,” he said.

Before Freeman takes the field, the training staff applies spatting tape to keep his ankle from rolling again. The aesthetics are not pretty. Freeman limps when he climbs the dugout stairs for early work. He limps when he jogs onto the field for pregame introductions. He limps pretty much all the time once the game begins.

“Ever since I came over here, everyone said, ‘Watch what this guy will play through, you’ve never seen anything like it,’” Kiermaier said. “That was back in August, and here we are in the most crucial games of the year. For him to do what he’s done, absolutely amazing.”

The injury prevents Freeman from bending the joint at the top of his ankle. Every step is a challenge. The discomfort was significant enough that he exited early in Game 3 of the National League Division Series. He could not play in Game 4. In Game 5, Muncy called a mound meeting to give Freeman a breather after a tricky play at first base. He might not play on Monday and he might not be able to appear in three consecutive games in New York.

On Sunday, facing a team that had blitzed the Phillies in the previous round, Freeman helped his club land the first strike. The Dodgers understood they might not see Senga for long. The hitters repeat a mantra when facing a starter on a tight pitch count: “He’ll go as long as we let him go,” as Muncy explained before the game. The group knows it can force an opposing manager’s hand by stitching together quality at-bats. “If we put together a bunch of really poor at-bats, they’re probably going to keep running him out there,” Muncy said. “If we put together a bunch of good at-bats and score some runs, get a lot of traffic on the bases, we probably won’t see him too many times.”

Senga was erratic at the outset, unable to command his fastball or forkball. Betts, Freeman and Teoscar Hernández loaded the bases with walks. Muncy stroked a thigh-high cutter into center field. Freeman had taken a hefty lead, far enough that third-base coach Dino Ebel waved him home. Every step looked painful. Mets first baseman Pete Alonso cut off the baseball, which prevented Freeman the indignity of attempting to slide. Instead, he found Betts waiting for him, arms outstretched. The 170-pound outfielder braced for impact from his 220-pound teammate.

“Luckily I lift weights so I was able to hold him,” Betts said. “He’s giving us everything he has.”

Freeman wore something between a grimace and a grin as he emerged from Betts’ grasp. He hobbled his way back to the dugout. He still had a couple more hits left to give.

“It’s not going to get better,” Freeman said. “But I think we’re at a good point where it’s not going to get worse again. Unless I roll it again.”

He plays like there is no tomorrow. Because when tomorrow comes, he might not be able to play.

(Photo of Freddie Freeman and Mookie Betts: Harry How / Getty Images)