Editor’s note: Live Nation / Ticketmaster, a dominant force in the live concert market, from venues to promotion to ticketing, was sued on antitrust grounds by the U.S. Department of Justice in May. Long-simmering anti-Ticketmaster sentiment crested with a major fiasco during presale for Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour in 2022, leading to a congressional scolding and, finally, the current DOJ action, which has not yet been resolved. We asked longtime music writer and historian Jim Washburn to give an account of what ticket-buying was like before Ticketmaster, and before the internet.

“Good afternoon, young man. May I help you?”

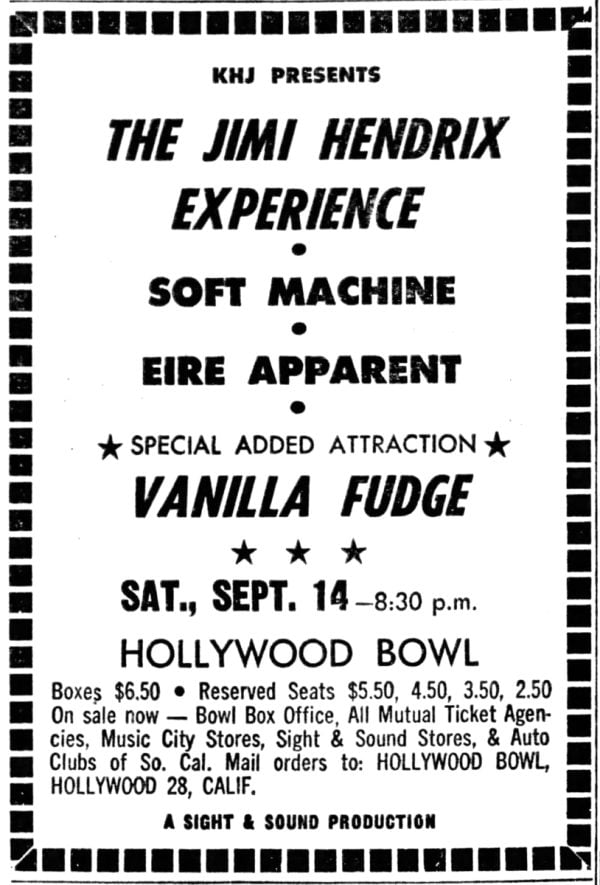

“Yes, thanks, ma’am. I’d like six peanut clusters and two Jimi Hendrix tickets, please.”

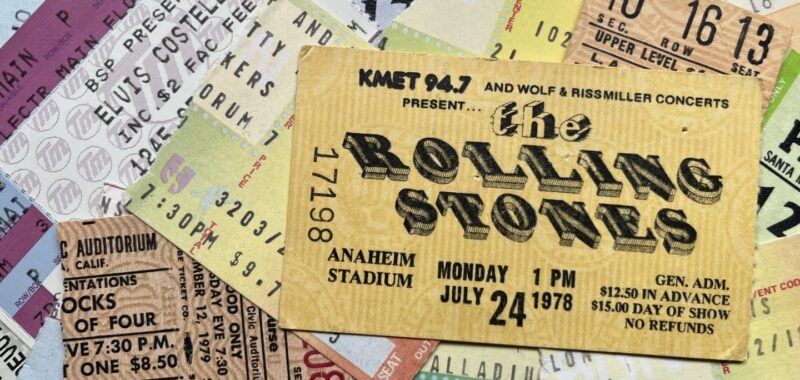

That 13-year-old young man was me in 1968, and that’s pretty much what buying concert tickets was like then. In Southern California, you’d either get your tickets from the event box office, or at a Mutual Ticket Agency, which had outlets wherever they could put one: department stores, Clifton’s Cafeterias, college campuses and all manner of mom-and-pop shops.

In my case, that was the See’s Candy shop at La Mirada Mall, where I was usually helped by a matronly woman with her gray hair in a bun, who likely didn’t know Jimi Hendrix from Jiminy Cricket. You’d tell her the artist, date and venue. She’d call the Mutual Agency’s Los Angeles headquarters to see what was available, fill in ticket blanks with your seat numbers and such, and you’d pay the face value of the ticket — $4.50 in this case — with no service charge.

The Mutual agency had been around since at least the 1930s, and it was still working pretty well in the late 1960s. But it was a rapidly changing world. The first concert I bought tickets for was Cream and Spirit at the Anaheim Convention Center in March 1968. My stepdad thought “concert” meant “society event,” and made me wear my J.C. Penney’s burgundy suit with a clip-on tie, ideal attire if you enjoy having hippies laugh at you. Thankfully, Dad had relaxed his dress code by that summer, when I was seated in a sweltering dirt field amid some 60,000 seemingly psychedelicized folks at the Newport Pop Festival, there to see Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, the Byrds and other rock avatars for $4.50.

The following year’s Woodstock festival and its subsequent film were a major accelerant to the live music scene, and to ticketing. When 1955’s “Blackboard Jungle” had opened with Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” blaring from movie-house speakers, it was a clarion call for kids who’d been waiting forever for music they could call their own. The Woodstock concert film was that on steroids, plus acid and weed. Its audience had grown up seeing their heroes assassinated, their friends shipped home in body bags and fellow students shot dead on college campuses for protesting. Now they had music that spoke to and for them, delivered via the loudest damn amplifiers anyone had ever heard.

A lot of us thought the questing music of the 1960s would lead to a utopian era of peace, love, flying cars and computers that could solve any problem. We settled for Ticketron.

The Ticketron era

Founded under another name in 1966, and functioning pretty well by the 1970s, Ticketron was the first successful computer-based ticketing system. There was certainly a need for it. As nice as the folks fumbling with the phones at Mutual agencies were, there was no way they could cope with the burgeoning crowds now seeking concert tickets. Had you seen the Who in 1968, you’d have been among maybe 1,500 hardcore fans, but by 1970, the Who were playing in arenas and stadiums, sometimes to more than 30,000 people.

Ticketron outlets were most often found in upscale department stores, such as the Broadway, May Co. and Robinson’s, and generally located deep in the stores’ customer service nook. Some had competent, trained staff who were sensitive to music fans’ longing to get the good seats before they were snatched up at other outlets. But some employees seemed to revel in frustrating the rockers infesting their tony store: “I’ll be right with you, dear, as soon as I’ve shown this couple our full array of gift-wrap paper.” Meanwhile, entire sections of concert seats would vanish.

That’s one reason why many fans chose to join the line at a concert venue’s box office, another reason being the perhaps mythic assumption that box offices had the best tickets. But no one shunned Ticketron to avoid the service fee — it was only 25 cents — or the convenience fee — since there wasn’t such a thing yet.

Ticket prices, meanwhile, had only moved up a buck or two in the early ’70s. Consequently, fans were outraged in 1974 when prices for Bob Dylan and the Band’s arena tour were jacked up to $8 and $9.50. But what performers and promoters noted was that, outrage or not, every show sold out and scalpers were getting record prices for tickets.

Scalpers enter the scene … and ticket prices rise

That was the first spark igniting the quick and apparently never-ending climb in ticket prices. When scalpers started to get $200 or $300 for tickets with a $15 face value, bands, promoters, venues and other stakeholders saw that as money that should be going into their pockets, not some scuzzball street vendor’s.

As a result, deadpans longtime concert-goer Matt Rosney, “Not that much has changed, except the decimal point. In 1975 I was paying $6.50 for a Stones’ ticket; now it’s $650 if I’m lucky.”

I’m mixing some different voices into the story at this point, because I became a music critic in 1983 and for the next quarter-century scarcely ever had to pay for the hundreds of concerts I saw. Poor me. So I asked friends and Facebook friends to weigh in with their experiences.

Philadelphia-raised Matt has seen the Rolling Stones in six different decades, beginning when he was a young teen in 1966: “I went with my mother and brother to Atlantic City. While they shopped or something, I spent one dollar and three cents tax to see the Stones in the Marine Ballroom on Steel Pier. They only played six songs in a half-hour set, with the audience screaming and going nuts, and I told myself, ‘I need more of this!’”

Matt hasn’t missed a Stones’ tour since, and once managed to see 19 shows on a 25-city tour. For the band’s 1969 jaunt, he had to drive to where the distant shows were a month early to try to buy tickets. When the Stones next toured, in 1972, Matt learned that if he could get the Ticketron code numbers for their gigs in other cities, he could buy the tickets right from the Ticketron outlet in a Sears store in Philly.

The communal side of standing in line

Matt and several others told me that one thing they miss about those days is that, alongside the competition to get good tickets, there was also a lot of camaraderie. When you’re in a queue sharing a joint or bota bag of wine with people as nuts about a band as you are, you sometimes form lasting friendships. One of Matt’s line-made friendships was with a huge collector of Stones memorabilia, who in turn was friends with the band’s security manager, who would sometimes get them into shows.

On the West Coast, Orange County teen Andrea Waters first saw the Stones at the L.A. Forum in 1972, and the following year spent a night in a sleeping bag in the Forum’s parking lot to get tickets for a benefit concert the Stones headlined. (She was amazed when famed concert promoter Bill Graham himself handed out the ticket slips in the morning.)

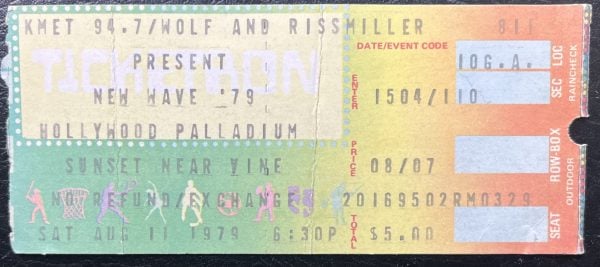

Like Matt, Andrea hasn’t missed a Stones tour since then. Sometimes the ticketing was done by mail order, and — taking a tip from a friend who’d mail in for TV game show prizes — she used colorful, hand-decorated envelopes labeled “Pick Me!” But it was Ticketron, and then Ticketmaster, outlets she had to deal with for most of the rock concerts she attended.

“That involved running at full speed through the local Broadway or May Company to the floor with the ticket counter,” she recalls. “They frowned on running, but that never stopped us. Once there, my friend Mike and I usually brought a clipboard with a sign-up sheet — like we were officials — so people wouldn’t try to jump their place in line.

“Unlike the old ladies at the May Company, at the Tower Records stores the Ticketron, and later Ticketmaster, crews really knew what they were doing. The problem was everyone knew that, and there’d be a hundred or more people lining up at Tower before they opened, so your chances could be dim there, too. We lucked out, for a while, when we found a Ticketmaster outlet in an out-of-the-way stationary store. Of course, people found out about that before long.”

When the Stones toured the U.S. in 1978, Andrea and some friends took to the road to catch several of the shows, and made some far-flung new friends in the queues. Matt Rosney was still doing the same, and at the Stones’ Cleveland show that year the two met and clicked. After clicking even more when they both turned up at subsequent shows in various states, Matt eventually moved west, and Andrea became a Rosney when they married in 1983. Forty-one years later, they’re still hitched, are grandparents, and still joined in the ticket scramble on the Stones’ current tour.

Ticketmaster, before the internet

These digital days, it’s not entirely surprising that a number of people I spoke with refer to the Line Nation-aligned Ticketmaster as Ticketbastard. But back in the service’s brick-and-mortar heyday, a lot of people on the business side of the counter did their best to make it work for ticket buyers. Lorraine Chambers, a writer and editor at the Hollywood Times, was part of the Ticketmaster crew at the Costa Mesa, California, Tower Records two decades ago.

She says, “We operated like a great assembly line, with a precisely delegated setup.” That entailed prepping the hopeful buyers in line outside: issuing wristbands; pre-checking IDs; instructing buyers to have cash and credit cards ready rather than fishing them out at the counter; and requesting they be quiet inside, so everyone’s orders could be heard clearly.

“Our goal was to keep the Ticketmaster machine printing out the most tickets possible before a show sold out,” Lorraine says. “The last thing we wanted to hear was a buyer moaning when that happened.”

Getting creative in search of tickets

I’ve heard several stories of other means of getting into shows. One couple mixed a gallon of screwdrivers in a plastic milk jug and traded it for tickets outside a multi-act stadium concert. One less consumer-minded person sold rabbit droppings as hashish outside a Tom Verlaine show. In more than one instance, people got to the front of a ticket line by carrying pizza boxes and saying they were making a delivery to the box office.

And then there were the Grateful Dead fans. In 1978, the Dead recorded a song called “I Need a Miracle,” and it became a mantra for fans who followed the band from city to city but lacked tickets. Sometimes they’d find someone with spare tickets; sometimes a sympathetic stagehand might slip them in a side door; but most often they’d find a poorly guarded fence to scramble over by the dozens.

That was at least more civilized than the heyday of rock festivals, when hordes would tear down parameter fences. As then-young concert-goer Mike Ritto put it, “Palm Springs Pop Festival: no tickets; got in free when the fences came down. Newport Pop Festival ‘69, Devonshire Downs: no tickets; got in free when the fences came down.”

Sometimes serendipity gets the job done. When Leonard Cohen’s final tour made its way to Seattle in 2013, my friend Karl Zwick went to the theater ticketless because he usually lucked out buying last-minute unclaimed comp tickets from the box office. He had no such luck this time, and was even less cheered when he saw a woman simply give away her two spare tickets to a man with a laminated “I Need Tickets” sign hung from his neck. Karl recognized him as a scalper he’d seen outside other shows. Since the fellow had paid nothing for the tickets, Karl offered him face value, $50, for one, but he insisted on $100.

“Then a guy who’d seen this came up to me a minute later and asked if I needed a ticket,” Karl recalls. “I said, ‘Hell yes,’ and then he quizzed me with questions like, ‘Where was Leonard born?’ ‘What’s the title of his second album?’ I guess I passed. He pulled a small stack of tickets from his pocket and handed me one.

“It turned out he was Leonard Cohen’s road manager. He didn’t like scalpers, and told me in a not too threatening voice, ‘If it’s not you in that seat, I will find you.’ And he did come out from backstage before the show started, saw me in the seat, shook my hand and said, ‘You’re a man of honor.’ That’s something I’ve never heard from Live Nation.”

Ah yes, Live Nation. They don’t get, or give, much love. Matt and Andrea Rosney certainly have no fun navigating Live Nation’s Ticketmaster site. Matt doesn’t like the surge pricing, where a ticket’s cost can suddenly lurch upward based on demand. He doesn’t like the convenience fee, so named because you have the convenience of buying tickets on your phone or home computer, without Ticketmaster factoring the massive convenience it is for them to not be paying for computers, printers, ticket stock and people in a zillion physical locations.

And don’t even get Matt started on the service fee. Oh, what the hell, let’s: “On my Stones ticket for Las Vegas, the service fee alone was $110. What service did they provide? Well, it hurts when I sit down. That’s the service they provided.”

(Grateful Dead crowd photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)